introduction to ...

the Masoretic Text and the Septuagint

by: Tim Kelley

December 30, 2015

The New Testament (NT) writers make many references to the ancient texts that Christians traditionally call the “Old Testament” (OT), or what Judaism refers to as the Tnakh1. You don’t have to look far in the text to see a verse that says something to the effect of “… it is written in the Prophets … “or "… the words of the prophets agree …”. One very memorable reference was made by the risen Messiah as He was walking with His disciples on the road to Emmaus when He said -

NKJ Luke 24:44 ..."These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me."

Then there is the verse that puzzles many who believe Yeshua “did away” with God’s law -

NKJ Matthew 5:17 “Do not think that I came to destroy the Law or the Prophets. I did not come to destroy but to fulfill."

According to my “quick” count, the NT writers made over 70 individual references to the OT text.

Why is it that these ancient texts were referenced so much? Why did the NT writers depend on them to substaintiate their words? It’s because they believed these words were inspired by God himself. The apostle Paul wrote -

NKJ 2 Timothy 3:16 All Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instruction in righteousness,

At the time Paul spoke these words the NT had yet to be compiled, and in fact, the individual letters that would later become the NT were still being passed around from congregation to congregation. Therefore Paul must have been speaking about the words of the OT.

But what OT words was he referring to? Better yet - what scriptural text - or body of texts was he referring to? After all, there were at least two different sets of texts available at that time - the ancient Hebrew texts of the scriptures and the Greek translation of the Hebrew texts that is called the Septuagint (abbreviated as "LXX"), and the NT writers used them both.

For instance, the first two chapters of the book of Matthew contains four quotes from the OT - Matt. 1:23 (Isaiah 7:14), Matt.2:6-7 (Micah 5:2), Matt. 2:15 (Hosea 11:1), and Matt. 2:18 (Jeremiah 31:15). All of these are very similar to the corresponding text of the Hebrew scriptures, but when you come to the next quote in Matt. 3:3, the text varies somewhat from what we see in the Hebrew scriptures, but nearly matches word for word the English translation of Isaiah 40:3 as it is found in the Septuagint. Another example of the writer’s use of the LXX is Matthew 15:9 which in the KJV reads:

KJV Matthew 15:9 “But in vain they do worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men.”

This is a quote from the later part of Isaiah 29:13 which in our Hebrew text reads:

JPS Isaiah 29:13 “… and their fear of Me is a commandment of men learned by rote;”

But in the LXX reads:

LXE Isaiah 29:13 “… but in vain do they worship me, teaching the commandments and doctrines of men.”

Thus we see that the NT writers used both bodies of text, choosing between them the one that best fit the point they were trying to make.

The purpose of this study is to give an introduction to the Septuagint as well as the Masoretic text - the body of text we now consider to be the Hebrew text. We will discuss the fact that today there is no “original” text, give a brief history of each text, and then finish by discussing the reliability of each text. We will not be discussing the New Testament in this study.

The Original Text -

You’ve probably heard the term “the original Hebrew” and thought that it is what you might find if you went to a Hebrew Interlinear, the Strong’s Concordance, or a Jewish Tnakh. But that’s not really the case. The only time you have an original of something, especially a manuscript, is when you have the one that was actually penned by the author. If you were to make a copy of the original, you now have a copy and an original. If you were to discard the original, you would be left with only the copy. In the days of computers, printers, and copy machines, it’s oftentimes possible to make a copy that looks almost exactly like the original, but for the trained eye, it’s not hard to distinguish between the two. A few years back, I was entering into a contract with a builder to construct a duplex. When signing the documents, the builder asked me to sign using a blue ink pen. I asked why and he said it was so he could distinguish the original document from the copy (since most copiers copy in black & white). That’s how good present day copiers perform their job. But it wasn’t always like that.

Before the days of the printing press, copies of manuscripts were made by hand, with the copyist studying the words of the original document, and then writing those words on another piece of paper (or parchment). If for some reason he could not read a word from the original, he might make an educated guess as to what the word might be then write it to his copy. If his guess was wrong and it were to get by the proof-readers, it might never be caught; and when that copy is eventually copied by another copyist, when he got to that word, unless he had a reason to question it, he would copy the incorrect word onto his copy as well. What’s more, if the original text were to get discarded, it’s unlikely the error would ever be discovered.

With that in mind, what might we consider to be the “original” text of the Bible? Better yet, when was the “original” compilation of texts put into one manuscript or collection of texts? In his commentary on the source of the Masoretic Text, E.W. Bullinger’s “Companion Bible” states that the earliest compilation of biblical texts was as a result of the Men of the Great Synagogue. He writes:

“The Text itself had been fixed before the Massorites were put in charge of it. This had been the work of the Sopherim (from saphar, to count, or number). Their work, under Ezra and Nehemiah, was to set the Text in order after the return from Babylon; and we read of it in Nehemiah 8:8 (compare Ezra 7:6, 11). The men of "the Great Synagogue" completed the work. This work lasted about 110 years, from Nehemiah to Simon the first, 410-300 B.C.”

The chart on the right shows the relative timing of the

creation of the various biblical texts in relation to the life of Messiah

Yeshua. You’ll notice that the Septuagint was completed about 150 years before

His day, and that the Masoretic text was completed nearly a thousand years

later. Today we are at least 2300 years away from what might be considered the

“original” text of the OT (the work of Ezra and Nehemiah), and probably 3400

years away from the original manuscripts of the Decalogue, the five books of

Moses. The NT writers were at least 350 years away from the ‘original’ text

themselves. To put that into perspective, consider the fact that we today are

only about 220 years away from our founding documents - the Declaration of

Independence and the Constitution.

Did the NT writers have access to those original manuscripts? More than likely not, for ink on papyrus does not last very long. Plus, because most manuscripts contained the name of God, it was the Hebrew tradition to honor the name by burying the texts when they were no longer readable. If then, they did not us the original manuscripts, what manuscripts were the NT writers reading from? They were reading from copies - probably copies of copies - of the ancient Hebrew texts, unless - as we’ve already seen - they were reading from copies of the Septuagint.

Were the copies of the original Hebrew manuscripts accurate? Various studies have shown that they probably were. What’s more, Paul’s statement in 2 Timothy 3:16 as well as the fact that the NT writers referenced those copies provides even more evidence that they were - at least until the end of the first century. After that point there appears to be minor alterations to the text as evidenced by the recent discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and by differences in the various manuscripts of the Masoretic Text.

The Masoretic Text -

At about 500 CE, a group of Jewish scribes set out to produce a Hebrew “bible” of sorts for the Jewish people who were scattering to the four winds. These scribes were called “Massorites” - a word that comes from the Hebrew word “massorah” which means “traditions”.

The London Codex BL MS Or. 4445, f. 61v - Public Domain

The goal of the Masorites was to produce a document that not only preserved the text, but also corrected known (or perceived) errors in the text. In addition to preserving the text, they added “vowel points” above and below the text so as to set the meaning of the words and to make it easier to read, thus helping to preserve the Hebrew language.

The Masorites gathered up as many of the various Hebrew manuscripts as they could find in order to do their work, but we must keep in mind that they were working from copies of copies . . . they did not have access to the “original” texts since those texts no longer existed. As they were doing their work, if they discovered an ‘error’ in the text, or felt the need to change the text for some reason, they faithfully copied the text of the “original” (which of course was a second or third generation of copies of the true “original”), but noted in the margins of the copy they were making what they believed to be the ‘correct’ reading. These marginal notes are what is called the “masorah”. Besides their changes, it’s becoming more and more clear (as evidenced by recent discoveries) that besides the errors the Masorites discovered and noted as they were making copies, there were changes or errors in the text from which they were copying (i.e. - earlier copies of the ‘originals’) that they either failed to discover, or that they did discover, yet chose not to correct - changes that may have crept in as a result of Jewish tradition.

The work of the Masorites continued for about 500 years and many generations. As a result, there were a number of “Masoretic Texts” that were produced - many of which do not agree. The most famous of the Masoretic texts is the Leningrad Codex which is the basis for most Jewish bibles and the basis for the “Old Testament” in most English language protestant bibles.

The Septuagint -

This Greek text of the Hebrew scriptures was translated between the years 285 BCE and 150 BCE, thus making it over 1100 years older than the Masoretic Text. Fragments of Leviticus and Deuteronomy have been found dating back to the 2nd century BCE, and relatively complete copies of the OT go back to the 4th century CE.

There are a number of legends, but few facts available as to its creation. The common thread is that there was a clear need for a Greek language version of the Hebrew scriptures in and around the area of Alexandria, Egypt where many Jewish people had settled after the Babylonian captivity.

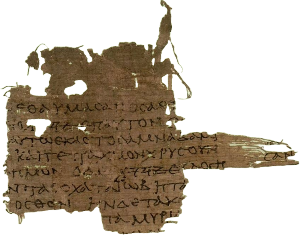

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 3522 by Sackler Library, Oxford - Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.org

After this area was conquered by Alexander the Great, the Greek language became wide-spread and eventually the Jewish people began to use Greek as their primary language. Because of the 300+ year influence of the Greek culture on the Holy Land, the LXX became widely accepted by the first century Jewish people, and as we’ve already seen, was used by, and had apparently become the preferred source of OT quotes by the NT writers.

Besides being written in a different language, probably the biggest difference between the LXX and the MT is that the LXX contains a number of “books” that are absent in the MT. In fact, the books of the Maccabees are absent in the MT even though they are the source of one of Judaism’s most treasured holidays - Chanukkah, the Feast of Dedication. Interestingly, Chanukkah is mentioned by name in the NT gospels (John 10:22), yet most Christian bibles omit the books of the Maccabees as well.

What the LXX gives to the modern day Bible student is a bridge to the 3rd century BCE texts of the Hebrew scriptures. This is important since it’s becoming more and more clear that the texts from which the Masorites made their copies had in some ways been altered – either intentionally or by mistake. Being that Greek is a much more precise language than Hebrew, once the original LXX manuscripts were written, it was much easier for copyists to make copies of the originals and to catch mistakes that may have been made by earlier copyists, thus preserving the purity of the text.

Which is More Reliable?

This debate started about 100 CE - obviously because of the influence of the Messianic believers on 1st century Judaism. Unfortunately, many Bible students believe that our OT comes straight from the “original” Hebrew. They are not aware that while most of it is derived from the Masoretic Text, the Hebrew to English “Christian” translators oftentimes used the LXX understanding instead of translating the Hebrew text when they thought the Hebrew was incorrect (Psalm 22:16 for example). Bible students are also unaware of the fact that after the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, parts of the text had been changed and if the change was discovered, it was noted by the Massorites, but those notes never became a part of our English bible texts. In his commentary on the Massorah, Bullinger explains why this is the case -

“When the Hebrew Text was printed, only the large type in the columns was regarded, and the small type of the massorah was left, unheeded in the manuscripts from which the Text was taken.

When translators came to the printed Hebrew Text, they were necessarily destitute of the information contained in the Massorah; so that the Revisers as well as the Translators of the Authorized Version carried out their work without any idea of the treasures contained in the Massorah (the margins); and therefore, without giving a hint of it to their readers.“

In fairness to the Masoretic text, we must remember that it is possible that the LXX could have been changed as well, but the chances of this happening are less likely, largely due to the before-mentioned preciseness of the Greek language and to the fact that older manuscripts of the LXX were not buried as were the Hebrew texts.

My conclusion is thus: Since there are no “original” texts of the Hebrew scriptures available for us to examine today, it is impossible to check the accuracy of our modern Hebrew (Masoretic) and Greek (Septuagint) texts against the Hebrew text that may have been available during the early 1st century CE. Thus the debate will continue. Never-the-less, more and more information is becoming available as archeological finds, such as the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, become more frequent.

Can we trust either text? Yes! According to the many articles I’ve read in preparation for this study, most agree that the differences between the two texts are minimal and the similarities are enormous, thus the intent of the OT writers is conveyed in either text; and when each text is taken as a whole, they generally agree.

Shalom Alecheim

Footnotes:

1 Tnakh is an acronym for Torah (instruction), Nevi’im (prophets), and Ketuvim (writings), i.e. - the Old Testament

Sources:

The Companion Bible; E.W. Bullinger; Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI; 1922; Appendix 30 available online at http://www.therain.org/appendixes/app30.html - history of pre-LXX text and how we got our Hebrew and English Bibles

http://www.theopedia.com/septuagint - dates of various LXX texts and fragments

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quotations_from_the_Hebrew_Bible_in_the_New_Testament - # of quotes from each text

http://www.ecclesia.org/truth/septuagint.html - textual variations between NT, LXX, and MT

http://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/bible-versions-and-translations/errors-in-the-masoretes-original-hebrew-manuscripts-of-the-bible/ - problems with the MT

https://theorthodoxlife.wordpress.com/2012/03/12/masoretic-text-vs-original-hebrew/ - corruptions in the MT

http://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-masoretic-text/ - the influence of Jewish tradition on the MT